The Power Of The Edit: Osei Bonsu And Ib Kamara

When it comes to creative work, we often focus solely on the finished product, rarely the process involved in making it. Nevertheless, as anyone working in these areas will know, it’s the decisions and the editing process that are integral to creating this finished product. In a conversation between stylist Ib Kamara and his fellow Central Saint Martins alumnus Osei Bonsu, curator of international art at London’s Tate Modern, the two discuss the power of the edit - how it shapes our understanding of culture and creativity.

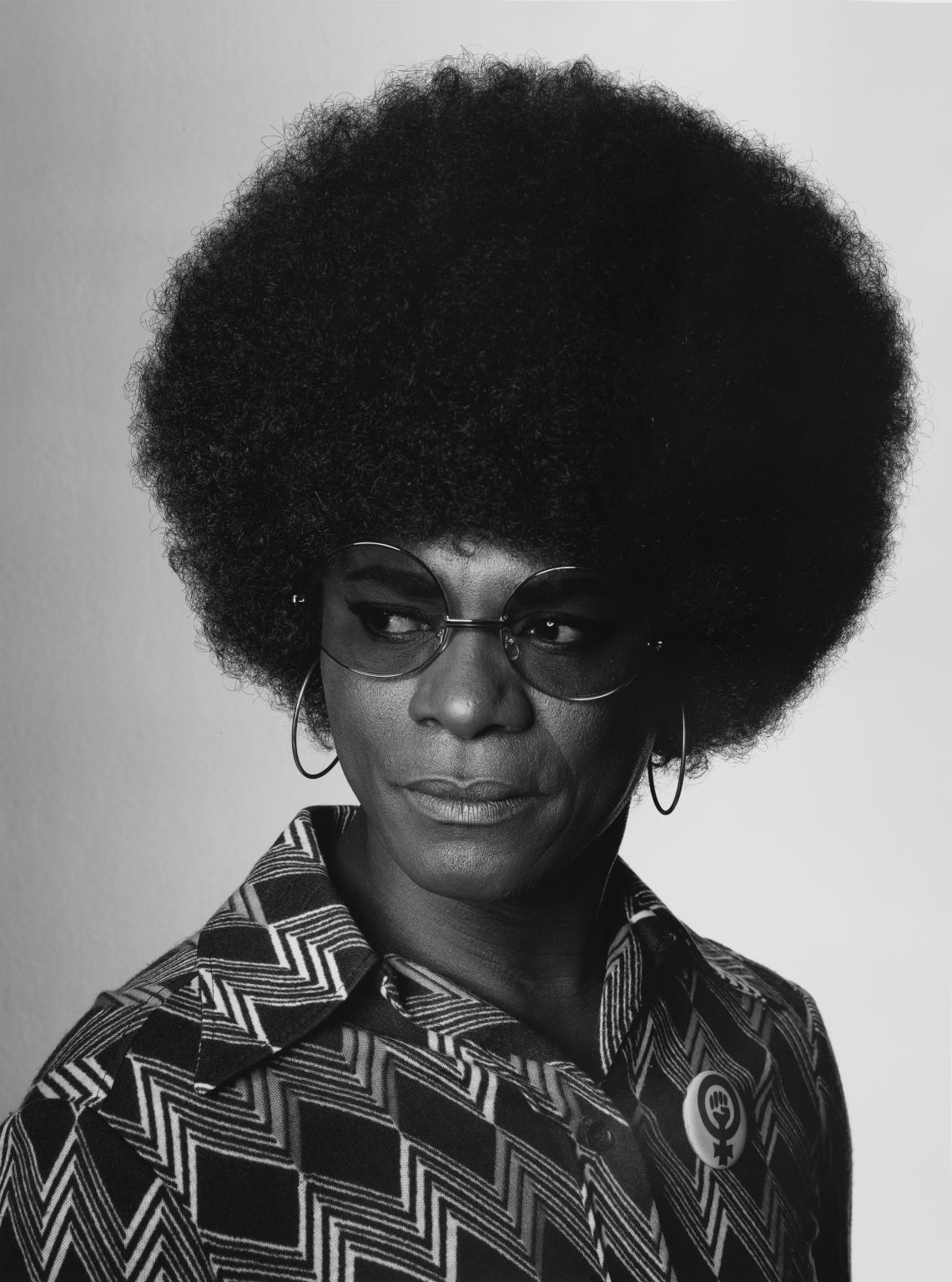

Samuel Fosso, Untitled from the series African Spirits, 2008, © Samuel Fosso, Courtesy JM Patras / Paris.

Osei: How would you describe what you do as a stylist?

Ib: Commenting on culture. There are so many things I reference in my work, and because I put them all together, it feels new in my head, and I hope it feels new in people’s heads too.

Osei: In my work as a curator of exhibitions, I think it’s about framing art in a historical context that allows that work to be understood and interpreted by audiences. For me, it’s about finding ways to explore narratives that might seem unexpected and give depth to a viewer’s experience of art. Curating is also about the interpretation, ensuring a work can be accessed from multiple perspectives, but more importantly about it’s about framing. This is where I see parallels between our worlds, to create stories with things that already exist in the world.

Ib: Coming out of Central Saint Martins I had this sense of pride for my roots and my background; of who I am as a Black man navigating this European gaze that I live in. I just wanted to create things that I felt were not there already.

Osei: For me, it was a similar beginning, it was about creating a space out of a void where we didn’t seem to exist. I’d grown up visiting museums that were very traditional, working in arts organizations that were primarily about attending to a particular kind of Western gaze. You would hear about famous European artists, but you wouldn’t necessarily hear about their counterparts in the non-Western world. The minute I started making exhibitions, it was about not only making those artists visible, but bringing attention to the nuances and cultural context around their work. As a curator, we don’t necessarily make images per se, but we provide a language for those images to exist in the world.

Ib: What was it that drew you to curating as opposed to making art yourself?

Osei: When I look at your work, I’m reminded why I’m not an artist. It takes a huge amount of commitment. You have to surrender everything to the work, and I think the artists who are truly successful consider themselves to be authors of their own vision. When you’re interested in curating and writing about art, you’re more interested in drawing parallels between worlds to create a singular idea.

This impulse has something to do with not being able to imagine yourself doing anything else. My interest in curating was driven by a need to make space for those who have been overlooked. When I think of the generations of artists who are emerging today, many of them are Black creatives coming into industries that are historically very white and elitist. We have a responsibility to improve this situation for others who have historically been excluded from our industries.

Arthur Jafa, Love is the Message, The Message is Death 2016. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York/Rome. This work was streamed online for 48 hours June 26-28 on Tate.org.uk.

Ib: That’s the generation I come from. We’re not going to wait back anymore and be told we need to climb the ladder. Because if I know I have something to say, why do I need to climb the goddamn ladder? For people of colour, it’s even harder to find the ladder!

Osei: Absolutely, but I think there’s also something to be said for the way in which images hold this particular kind of power too. For a long time, Black beauty has been consumed and celebrated in the media, but there were few Black creatives in positions of power; Black creatives getting to make decisions about how they want to represent themselves and their communities. With the Black Lives Matter movement, I think there’s a huge amount of change happening, but I think it can only happen when the stakeholders with power in our industries surrender some of that power to those who not only deserve the opportunity, but whose voices really need to be heard.

That takes me to the next question which is about the power of the edit. What’s the importance of editing and how does it add to the creative process? I imagine when you finish a shoot there are so many possibilities in terms of telling the story. How do you approach editing?

Ib: I’m very brutal when it comes to my work. I always like to present the best of what I can give to the world, because my work is not for me, it’s for people to consume, and I want them to consume the best things.

Osei: In the context of making an exhibition, you’re trying to find a way to tell a story. Often, it’s finding ways for multiple narratives to exist at the same time. I prefer exhibitions when you’re not following a particular route, but you’re following many at once; personal, political, psychological. Exhibitions involve a particular attention to the experience of the viewer, how they move through space and meet objects. Whether it’s the colour that the wall is painted, the interpretation text, or a particular frame you might use for a work, or even the spotlights. How do you know when the edit is complete?

Ib: I reference my notes and I look at the things I wrote and see if that’s what I’m seeing on the board - those little details I sketched or wrote in my book. If I see that in the work and it speaks to me, like how I saw the imagery in my head, then I realise: “Oh, we’ve completed the story.”

Osei: I’m curious to know what you think, as it’s something that fascinates me in terms of fashion images, about this idea of timelessness. We know that fashion images are published in magazines on a monthly basis. When you create an image are you trying to achieve a sense of timelessness?

Ib: I think every time I create a photo I’m trying to bring a timelessness to it, because it’s well researched and there are so many cultural elements taken from all over the world within a picture; this sense that everyone could relate to that beauty, or everyone can see themselves within that picture. To me, that’s timeless.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Passion Like No Other 2012. Collection Lonti Ebers © Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. This work will be available to view in the artist’s upcoming exhibition at Tate Britain, 18 November 2020 - 9 May 20201.

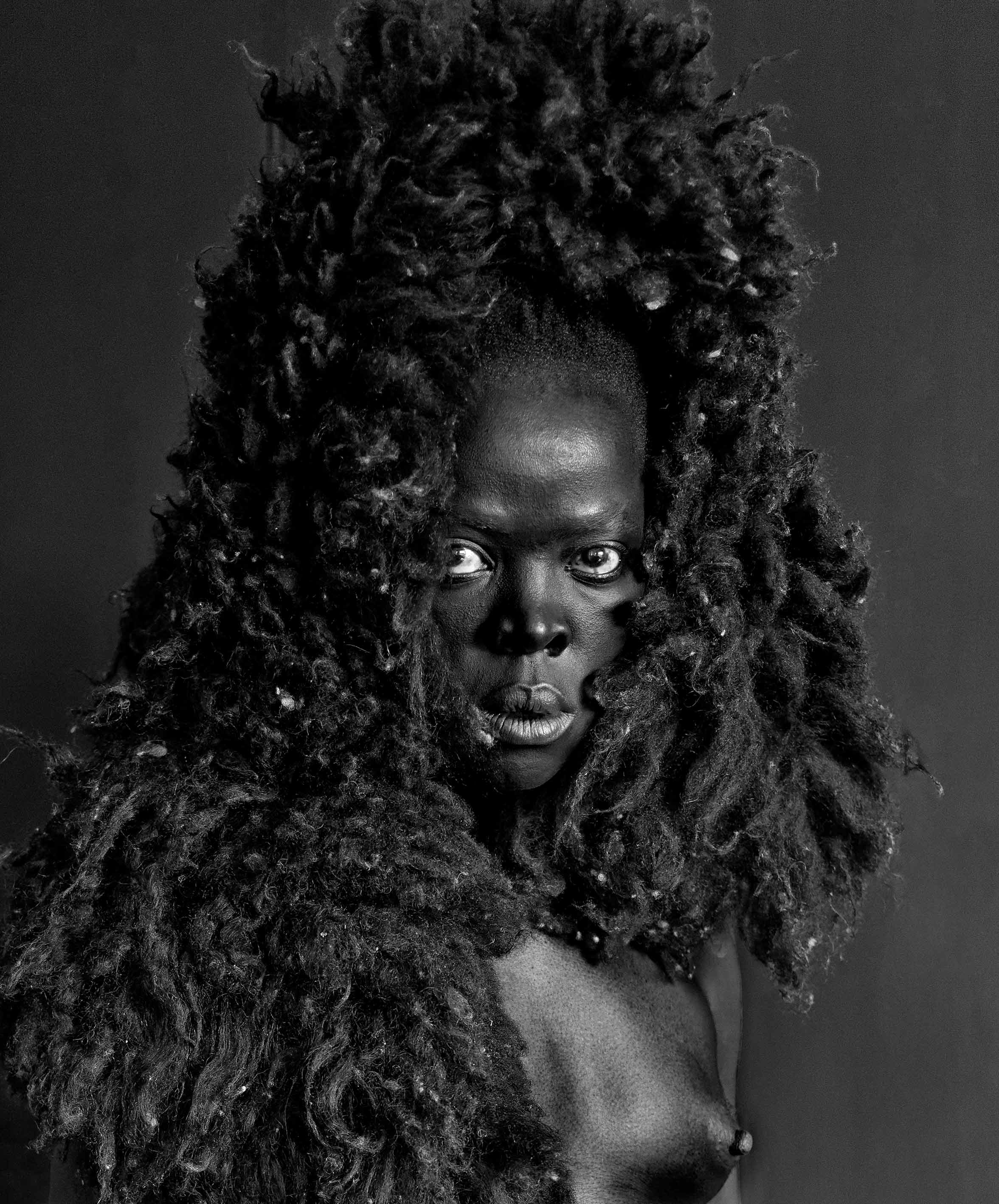

Zanele Muholi, Somnyama IV, Oslo, 2015. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York. © Zanele Muholi. This work will be available to view in the artist’s upcoming exhibition at Tate Modern 5 Nov 2020 – 14 March 2021.

Arthur Jafa, Love is the Message, The Message is Death 2016. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York/Rome. This work was streamed online for 48 hours June 26-28 on Tate.org.uk.

Osei: If there’s something powerful about the process of editing, I think it’s about giving yourself permission to be fully in control of your own vision, to visualise reality as you see it or as you might want to see it. At a time of social upheaval, I think it’s about staying true to your vision even when the world continues to try to supress and silence the voices of dissent. This was very evident in one of your first projects about Blackness and masculinity, Soft Power. How has your vision of fashion changed since then?

Ib: I’m 30 now, so I’m sort of refining the things I want to say even more. I woke up two days ago and I said: “I’m so happy I’m Black.” I love being Black. I love my history and I love my culture and I love my people. I would not want to be in this world if I wasn’t Black, because that’s the most beautiful thing in the world, and I’m a champion of it. For so many years I hated the way I looked, I hated my skin colour, because those were the things you were taught as a child, to not love your Blackness. At the age of 25 I started exploring who I am, and five years later, I’m so proud of being this African Black man in the world.

I’m trying to create representation for people after me - images that kids are going to look at and say: “Wow, I look like her, I feel empowered.” This is beyond editorials at this point - it’s about making a body work that shows us in beautiful, positive lights. Making imagery for us.

Soft Criminal (2018) photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman, designer and maker Gareth Wrighton, stylist Ib Kamara.

Images curated by Osei Bonsu

Portrait by Nicholas Hadfield for Boy.Brother.Friend, Issue 1, Spring 2020

Interview by Georgia Graham

Special thanks to Tate

Related Reading:

A Family Affair: Guest Edited By Ib Kamara

A Vision Of The Future: Ib Kamara

From the Root to the Tip, Black Hair Proclaimed

Mix It Up: Mischa Notcutt