Beyond Beats And Borders: The New Exportation Of African Music

Nigerian publication The NATIVE are the cultural commentators with their fingers on the pulse of the African millennial, offering a contemporary perspective on music, culture and style. Here, they discuss the current influence and popularity of African music around the world, and how this popularity brings with it a new set of conquests and concerns for African culture and the artists who shape it.

Mr Eazi, Tiwa Savage, Odunsi (The Engine), DJ Cuppy

“Africa Now”

For years, variations of this proclamation have been touted across the Western world, as European and American audiences increasingly engage with music and culture from The Continent.

This narrative has become the central talking point for Western media when engaging with international music movements. In May, Billboard ran a cover story with three of Nigeria’s brightest stars (Tiwa Savage, Mr Eazi and Davido) prophesying: “The next musical revolution is brewing in Africa”, but back in 2016, CNN detailed how African music: “finally has the world’s ear.” Though the narrative continues to be guided by the Western world’s constant re-discovery of international sounds and styles, modern African music has been making strides overseas for decades.

There is a robust history of African artists across genres, generations, and countries who reached the standard of success marked by a Western crossover. From jùjú legend King Sunny Adé, to the Grammy winning Angeliqué Kidjo, to Mama Africa Miriam Makeba, and the late Afrobeat creator Fela Kuti, who inspired respect and recognition with his socially and politically inclined music that would become the foundation of Africa’s most popular modern genere: afrobeats. Pioneers like 2Baba, Don Jazzy, and Wande Coal paved the way for the mainstream afrobeats sound that’s grown to popularity over the past 10 years with Nigerian acts like Wizkid, Davido, Mr Eazi, and Tiwa Savage carrying the mantle. These acts are who audiences outside of Africa are now familiarising themselves with, while an assortment of newer genres, sounds, and artists have emerged across the continent.

But what does crossing over look like for a new generation of African musicians? With the current exportation of African music across the globe, age-old issues are unearthed along with a new set of concerns. African music has gone global but Nigerian artists in particular have captured the world’s attention. Despite the signs of strides, whether popular African music has crossed over to the Western mainstream is still hotly contended. What is clear is the type of sounds and artists that are granted visibility on global stages. But when Western audiences and gatekeepers hyperfocus on a singular sound and conflate much of everything else with it, they run the risk of rendering African music a monolith and dismissing the diversity and dominance of other artists and sounds on their own turfs. There is, and has always been, more music brewing abroad.

While mainstream afropop acts have now connected to international audiences, a newer wave of artists amplified by the power of the internet and heightened international attention to African art are finding their footing. They’re circumventing both traditional industry and societal constraints and building their own platforms in and around the industry. Cultivating their crafts and communicating directly to their fan bases; forging their own paths to success. Though, they, too, still end up having to play by the rules they didn’t create.

Divergent styles have spawned from popular styles since then. Younger artists like Odunsi (The Engine), Lady Donli, and Rema are moving Alté and other alternative sounds past the margins of popular music. But it’s a wonder whether American audiences are open to that divergent ingenuity – let alone capable of identifying their distinctions, as many still conflate afrobeat with afrobeats – or simply pining for more of the same mainstream afropop sound that they’ve been introduced to. Herein lies the issue with Western powers having the vested authority to cherry-pick what and who gets acknowledged and championed from abroad.

Mr Eazi, Davido, Wizkid, Tiwa Savage, DJ Cuppy

In a 2017 interview with Afropop Worldwide, acclaimed Nigerian music video director Clarence Peters harped on the need for African artists to reclaim power over their narratives. “International doesn’t define us; we define what’s international,” he said. “If we wait for America to tell us, ‘Alright, you guys are there,’ then we will wait forever. But when we say to ourselves, ‘we are international, screw what anyone else says.” But the dimensions of that power dynamic within cultural exchanges aren’t that simple.

Despite this understanding American and European institutions, audiences, and perceptions still hold material influence over international successes. When Burna Boy’s acclaimed “crossover” album African Giant was nominated for a Grammy in the World Music Album, a conversation on the controversies of the category and the implications of Western institutions’ misinterpretation of international cultural productions resurfaced. With that came the broader question of whether African artists and audiences can secure ownership and authority, not over cultural productions they already own, but over their perception.

Once art is consumed, an exchange takes place, albeit not always monetarily or physically. The documented occurrence of cross-culture communication, primarily across the Black diaspora, is evidence of its borderlessness. But as music and culture continue to be shared beyond borders, who earns a profit and at whose expense? The music industry across many African countries face daunting challenges. Listeners on the content don’t buy music, bootlegging is still rampant, and many nations are dealing with a number of wide-ranging issues and instabilities across social, economic, and political spectra that bear direct and indirect influence on music and business. Volatility and voids in the market oftentimes result in African artists having to travel abroad to earn their worth.

But with the heightened visibility comes heightened expectations; Nigerian artists have newfound responsibilities in setting precedence and making sensible decisions from an artistic, economic, personal, and professional standpoints, that will have lasting effects across countries and careers. But responsibility also lays in the hands of consumers, industry leaders, writers, and documentarians as well. Creating and cultivating culture is a communal effort, as is innovating and preserving it. The question all parties should pose now is: what would it look like to generate a vision of success that eclipses the Western gaze? “I care about crossing over, but in the opposite way,” Burna Boy told Fader in 2019. “I want to come here and cross you over to where I am... Because where I am is the actual home of the beginning,” he added. “The reverse crossover.”

A “reverse crossover” or other renewed understandings of the concept can create space for a more fair exchange where artists stand to profit in both tangible and long lasting ways, where less is relinquished and more is earned. As Burna implies, a post-crossover world shouldn’t be bound to the limitations of singular-direction success. If the idea of crossing over is reconstructed to reflect a more expansive vision of connecting and co-existing, rather than cultural concession, yielding a more liberating space for success.

Beside the mountain of concerns are conquests worth celebrating as the music expands further and culture shifts on the continent and beyond. Crossing over has long marked the inflection point of African artists’ success – this position may very well be a launching pad, it is by no means the end point.

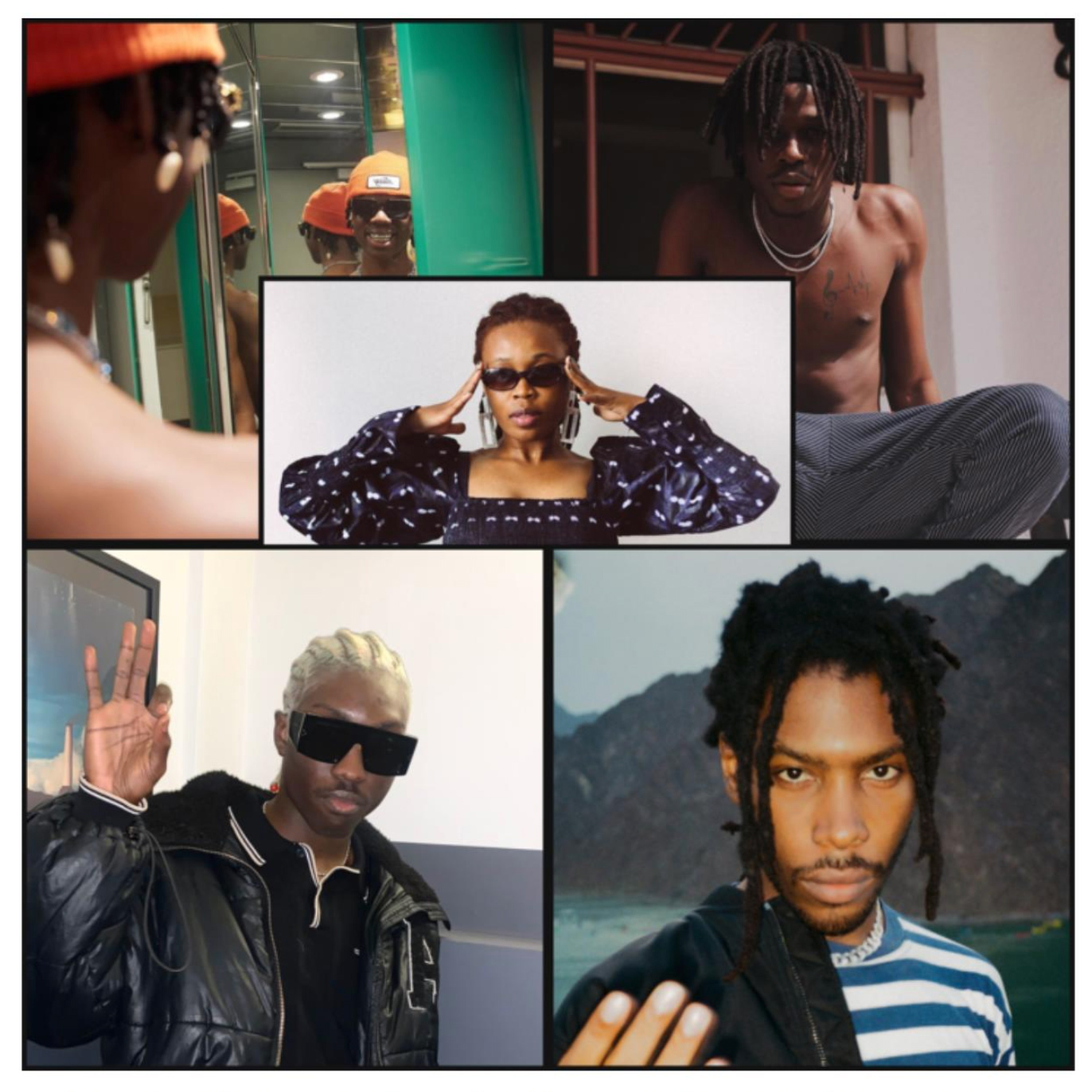

Rema, Fireboy DML, Lady Donli, Odunsi (The Engine), Cruel Santino

Words by Ivie Ani

Related Reading:

Homecoming And Browns Present: Ni Agbaye

“Ma People, Ma People”

Re-imagining Society: Nigeria’s New Generation

Homecoming And Browns 2020: Exclusive Online Panel Talks

See All Stories: