Come and See: Through The Lenses Of Kenneth Ize And Mowalola Ogunlesi

As Nigeria’s foremost purveyor of critical thought, The Republic is a Lagos-based publication delivering a view on contemporary Nigerian identity through the lens of art, politics, history and culture. Here, editor-in-chief Wale Lawal and author Boluwatife Akinro analyze the work of two of the country’s finest design exports: Kenneth Ize and Mowalola.

As Nigeria’s foremost purveyor of critical thought, The Republic is a Lagos-based publication delivering a view on contemporary Nigerian identity through the lens of art, politics, history and culture. Here, editor-in-chief Wale Lawal and author Boluwatife Akinro analyze the work of two of the country’s finest design exports: Kenneth Ize and Mowalola.

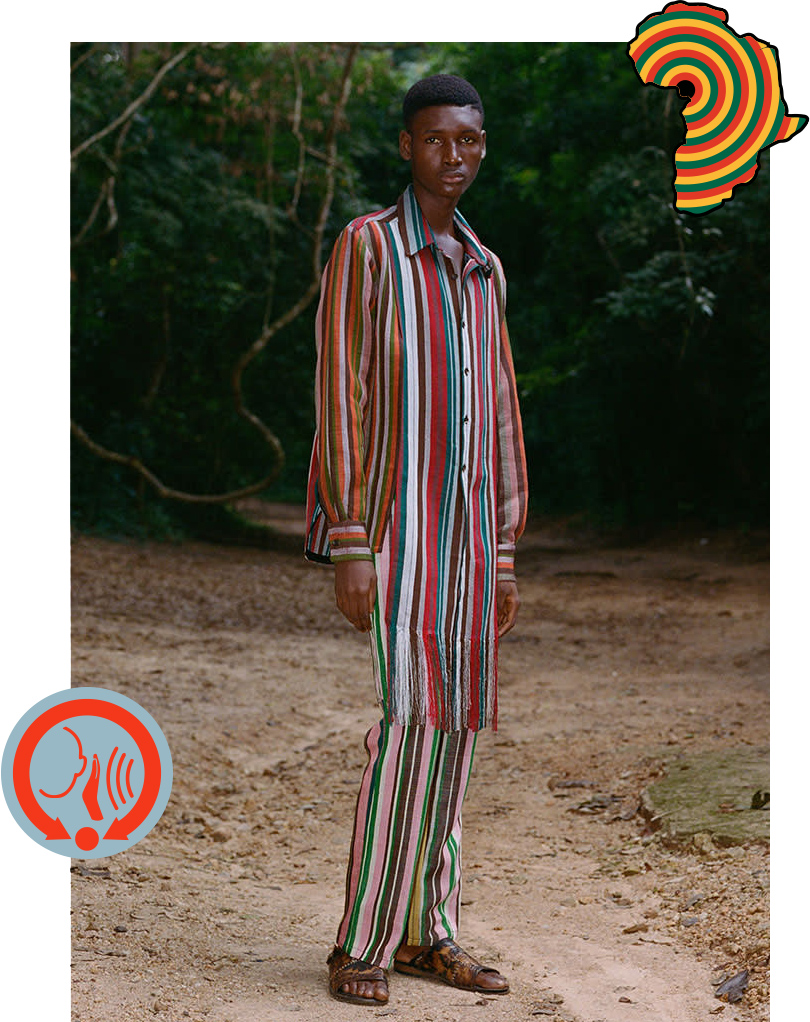

Kenneth Ize S/S 20 collection, photographers in Osun-Osogbo, Nigeria.

© Vincent Thibault.

Lagos-born, 29-year-old designer, Kenneth Ize, does not hide the cultural origins of his designs. His Instagram, for instance, is replete with images of African masquerades, sculptures and pre/post-independence dandies. His emphasis on detail and his specificity, is unsurprising, given his descent from a long history of cloth valuation in Africa. Colleen Kriger, in her study of cloth in West African History, has documented the particularity with which African buyers interacted with European merchants, preferring specific cloths in tune with the time, diligently inspecting imported cloth which they requested down to the name, manufacturer, fibre and colour.

Cloth has played a central role in African socio-economic relations with outside groups for centuries. Ancient communities like Oyo, Ijebu Ode and Benin produced cloth for export at ports in Benin, Allada and the Gold Coast to ready markets in Angola, Gabon and beyond the continent to the West Indies and South America, writes Kriger. However, with the advent of colonialism, imperialist agents deliberately erased centuries’ worth of such interactions to position Africa as unknown. Cloth made the transition from familiar currency to exotic curiosity, as African nations turned from trading partners to uncivilized subjects.

Kenneth Ize by Lakin Ogunbawo.

By re-imagining and re-purposing traditional looming practices, Ize not only restores suppressed history but also provides a model for engaging with such histories. Just as important to Ize as the ‘Made in Nigeria’ signifier are the people doing the making. In Ize’s work, his loomers are foregrounded, given credit as the culture’s regenerative capital, alternatively providing a way to engage with archives as dynamic forces. The inventive nature of his work emerges at a time where Africa is increasingly being looked to, particularly by its diaspora, as a source of restoration. What tends to underline such views is a belief that the continent has the answers to the questions that black identity often raises; that in connecting or re-connecting with the continent it is indeed possible to find oneself.

If such views require freezing the continent in a distant past, we can find in the works of artists like Ize a necessary realism. Ize, for one, does not bank on a mythical Africa but rather on what is available. The loomed fabric of his smart-cut jackets and tailored pants belie the pervasive idea that Africa has experienced a rigid rupture from its past. They recognize the continuity of history where the African present is inseparable from the social realities of the global modernization project. Clear in Ize’s vision is the belief that African heritage raises as many questions as it answers; that the past does not remain in the past but evolves with changing social contexts. Clearer even, in his engagement with the custodians of the culture he uses, is the fact that a rhetorical and ideological restoration of the continent must be accompanied by a material restoration. Resources from the global marketplace of African alterity must flow to its original creators to sustain these practices. The anthropologist Arjun Appadurai thinks of the past as a resource, and Ize exemplifies such thinking, to the extent that Ize re-introduces traditional looming practices to the world and, in turn, redefines such practices.

However, one could argue that the history that drives Ize’s work is what we can call acceptable or respectable history. Cloth and weaving practices, after all, are a part of the canon, cultures that have long been deemed worthy of study, worthy of the archive and, thus, worthy of preservation. Ize’s work is elegant but he is also drawing from histories, the acceptability of which are hardly ever questioned. These are not untold histories or histories of the unacceptable, as we see conceptualized in the designs of another British-Nigerian designer, Mowalola Ogunlesi.

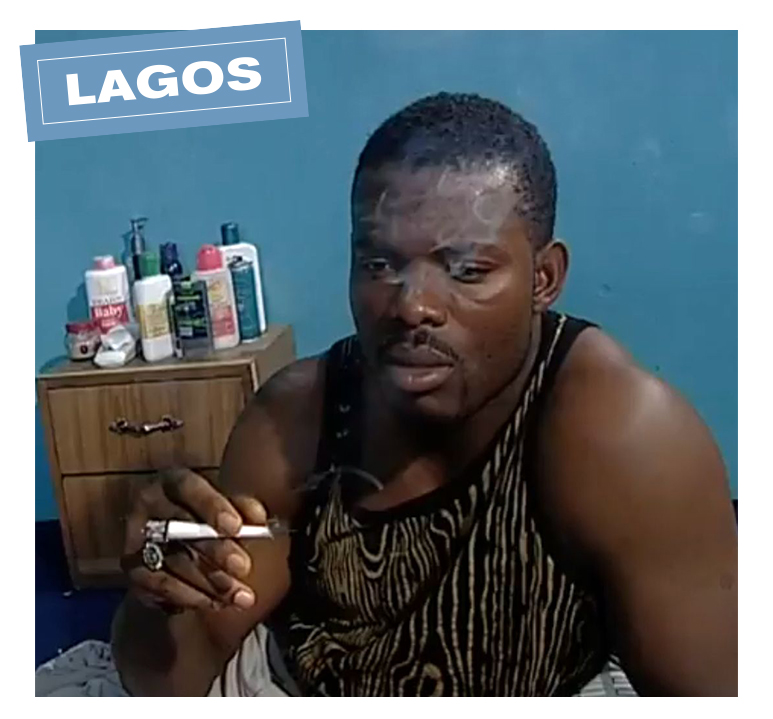

Like Ize, 25-year-old Ogunlesi’s eponymous designs are steeped in Nigerian cultural references so finely treated they are easy to miss. However, the two designers operate on vastly different planes: if Ize’s work draws from established tradition, Ogunlesi’s is inspired by a protean modernity, that is, a modernity that does not know just yet what to think of itself. Though her work is embedded in history, her work feels contemporary because it engages with a Nigeria that is still grappling with its own identity today, a struggle that is the very foundation of its largest cultural export: Nollywood. Known for its sacrifice of quality for volume, Nollywood has its own battles, ‘is it authentic?’ being the most prominent. After all, its name, which Nobel laureate, Wole Soyinka, has described as an ‘unprepossessing monstrosity’, is more Hollywood than N for Nigeria, as though to prepare audiences for scenes replete with Lagos-made American accents and sensibilities. For Soyinka, Nollywood, like much of Nigeria, needs to re-evaluate its preference for mass production and its reluctance towards refinement. Does the industry ‘still deserve to be associated with that second-hand clothes market tag,’ he asks in Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions, ‘or should it be with an evolving designer-cut production catering not for the lowest common denominator in taste but for more discerning audiences?’

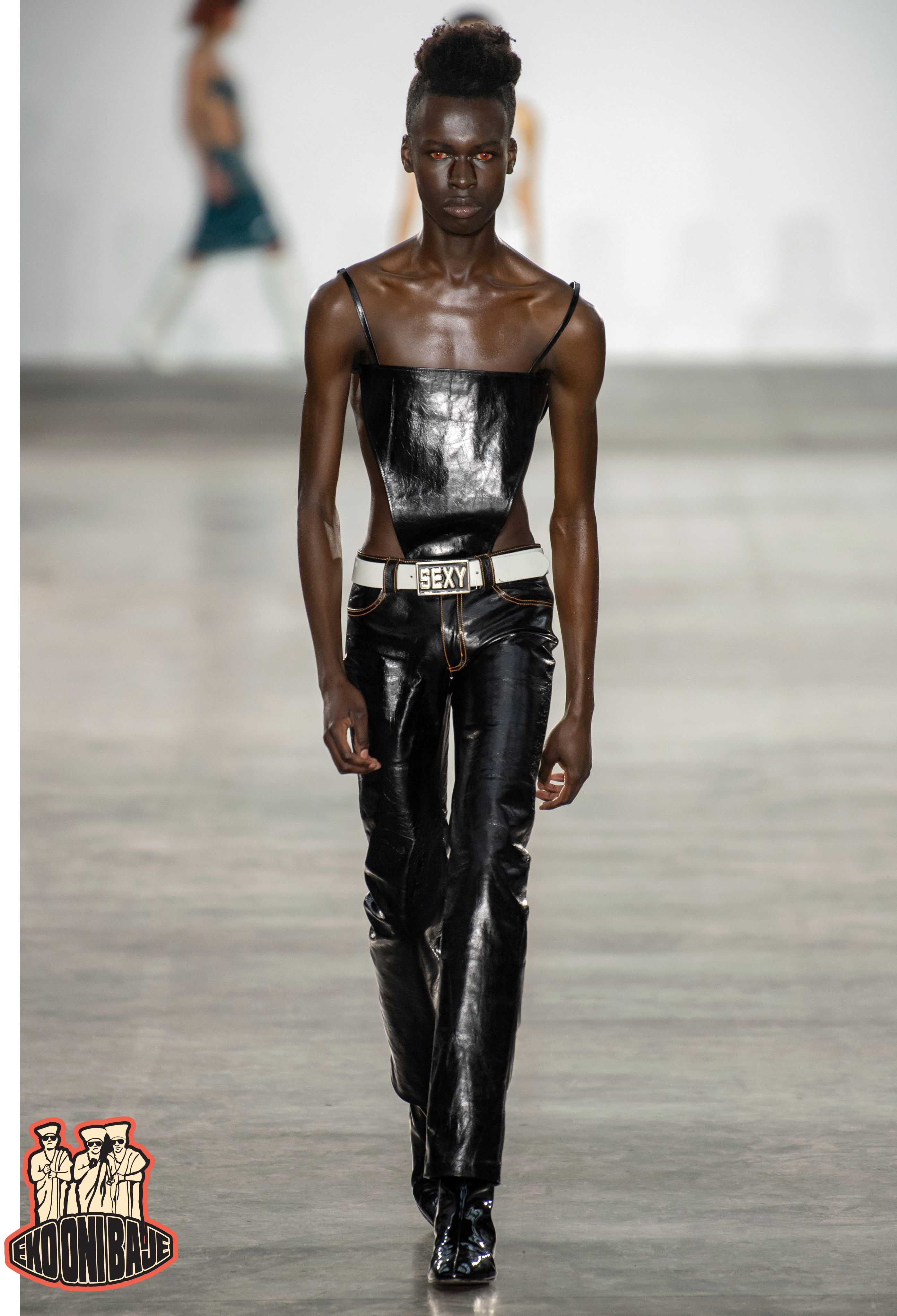

Clothing by Mowalola

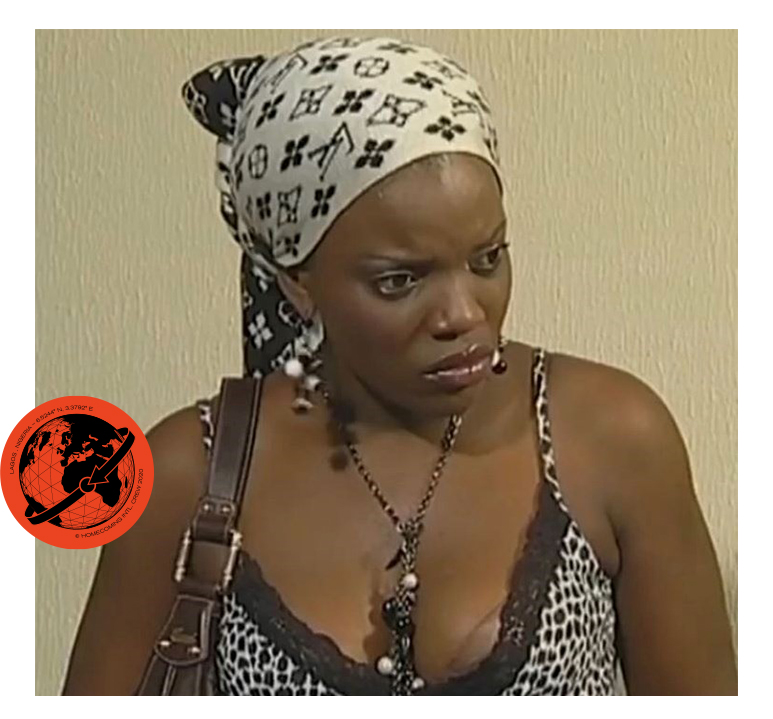

If specificity implies rigour, Nollywood and specificity are not often thought of as compatible. But what Ogunlesi has been able to do is elevate precise Nollywood cultures into spaces, from archives to catalogues to runways, that would otherwise deem them unacceptable. In this way, she follows the footsteps of artists like Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Zina Saro Wiwa, who have situated critical practice in Nollywood imagery. Like Ize, Ogunlesi also presents a distinct way of engaging with African history, but this time the lesson is for Africans themselves and concerns what Africans consider to be history. While Africans may criticize the world’s disproportionate interest in the continent’s distant past, Africans, too, are guilty of overlooking recent histories, especially those histories that exist beyond the traditional.

Images c/o Nollybabes

Ogunlesi is interested in a nearer past, which goes against the over-emphasis on pre-colonial African history found in the diaspora and the nostalgia for the independence era found on the continent. At the same time, the artist—whose blood-stained, image-strewn, slick leather and open-backed pieces invoke a raw, shocking, devil-may-care sexuality—relays stories of the shunned, the hidden, the tabooed. These are designs that evince an understanding that, in Nigeria, stories of liberated women, of queerness, of non-orthodoxy, are only useful insofar as they are material for conventional and erroneous moral lessons. For Ogunlesi, however, stories of the unrespectable are the story. Against historical narratives of savagery and crisis, and against equally reductionist counter-narratives of respectability, Ogunlesi’s vision of the unacceptable emerges more interesting and even more redeeming.

Compton In Africa by Kendrick Lamar,

taken from Lamar’s 2016 Grammy Performance